The Cashel connection to one of the greatest Grand Nationals of them all

Often dubbed the “Housewives’ favourite race”, where everyone fancies a flutter, the English Grand National holds a special place on the sporting calendar for anyone with even the most fleeting of interests in horse racing. Every April when the horses line up in Liverpool at Aintree Racecourse, the bookies till ring out and many households come to a stop for the nine and a half minutes or so, that it takes the equine heroes to cover the two circuits, before finally finishing in that long run home through the famous elbow.

But what many Cashel people may not realise, is that the town has a very real and strong connection to one of the most famous horses to claim victory at Aintree. A horse that to this day, can claim to be “one of a kind”, because not only did he win the famous race, on that famous day in 1928, he was the only horse that didn’t fall over the fearsome thirty fences. And that horses name was, most fittingly, Tipperary Tim.

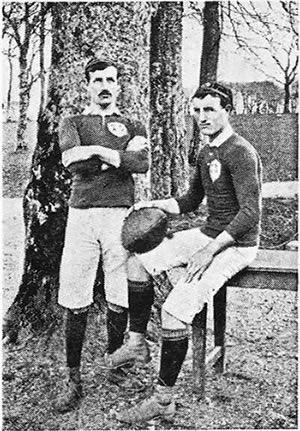

Tipperary Tim was foaled in Ireland in 1918, and his breeder was a Cashel man, named John (John Jo) Ryan. John Jo was a keen sportsman, and had more than horse breeding to his accomplishments. He was capped 14 times for the Irish rugby team, and along with his brother Mick, was part of the Irish rugby team that won the Triple Crown and the then Home Championship in 1899.

Ryan named Tipperary Tim in honour of another famous athlete from the area, and one of his own heroes, Dundrum runner Tim Crowe, who hailed from Bishopswood in the West Tipperary village. Tim was an extraordinarily successful distance runner, twice junior cross-country champion of Ireland, and he won sixteen national senior championships on the track, road and cross-country, and twice competed for Ireland in the International cross-country championships.

He competed in the Polytechnic Marathon in London in 1921 where only four of the 39 starters finished the actual course after Tim and others ran a mile off course. Despite that, he came home in sixth place. In 1926, as trainer, he accompanied the Tipperary senior hurling team, the All-Ireland champions, on a tour to the USA.

But back to the famous horse. Tipperary Tim’s sire was the British horse Cipango and his dam was the Irish horse Last Lot. His grandsire was the British horse St Frusquin (who had been sired by the undefeated St. Simon) and his damsire was British horse Noble Chieftain. The stud fee paid for Cipango was just £3, 5 shillings (equivalent to £189 in 2023). He was a brown-coloured gelding, and was been sold as a yearling for £50.

Tipperary Tim came into the ownership of Harold Kenyon, who put him into training in Shropshire, under the tutelage of one Joseph Dodd who noted that “he never falls”. But other reports said that he was capable of only one pace, and a relatively slow one at that. Tipperary Tim was tubed, that is he received a permanent tracheotomy, with a brass tube halfway down his neck to improve his breathing. He was stabled at Fernhill House in Belfast.

His first taste of Aintree came in 1927, when he took part in the Molyneux Steeplechase, in the November race meeting, without any success.

So, it seemed a little strange then when he returned to Liverpool less than five months later, to take part in a much more prestigious race, with a much stronger field, the Aintree Grand National. At the time he was ten years of age, and was ridden by amateur jockey Bill Dutton, a Cambridge-educated solicitor from Chester, who had left the profession to pursue horse-riding. The gelding named after the finest of the Premier County went to post as a 100/1 outsider and Dutton later recalled that a friend had told him before the race, “you’ll only win if all the others fall”. How prophetic a line that turned out to be!

The field in 1928 was the largest to date with forty-two runners starting the race. The going was very heavy and there was a dense fog, making things even more difficult for the big field. There were three false starts, after which the broken starting tape had to be knotted together. On the first circuit of the Aintree track the leader, one of the favourites, Easter Hero, mistimed the Canal Turn jump, causing chaos behind him. Rising too early he was stranded briefly on the fence before becoming trapped in the ditch, which preceded it. The next three horses, Grokle, Darracq and Eagle’s Tail were brought down by Easter Hero. Of the remaining runners, twenty-two remained at that time, twenty refused to jump the fence. The pile-up was described by racing historian Reg Green as “the worst ever seen on a racecourse”. Only seven horses with seated jockeys emerged from the incident to continue the race. One of these was Tipperary Tim as Dutton had chosen to take a wide route around the outside of the course, avoiding hazards that had brought down other jockeys. Because of the fog the majority of the audience were unaware of the incident at Canal Turn. By the second jumping of Becher’s Brook only five horses remained in the race with Billy Barton leading ahead of May King, Great Span, Tipperary Tim and Maguelonne.

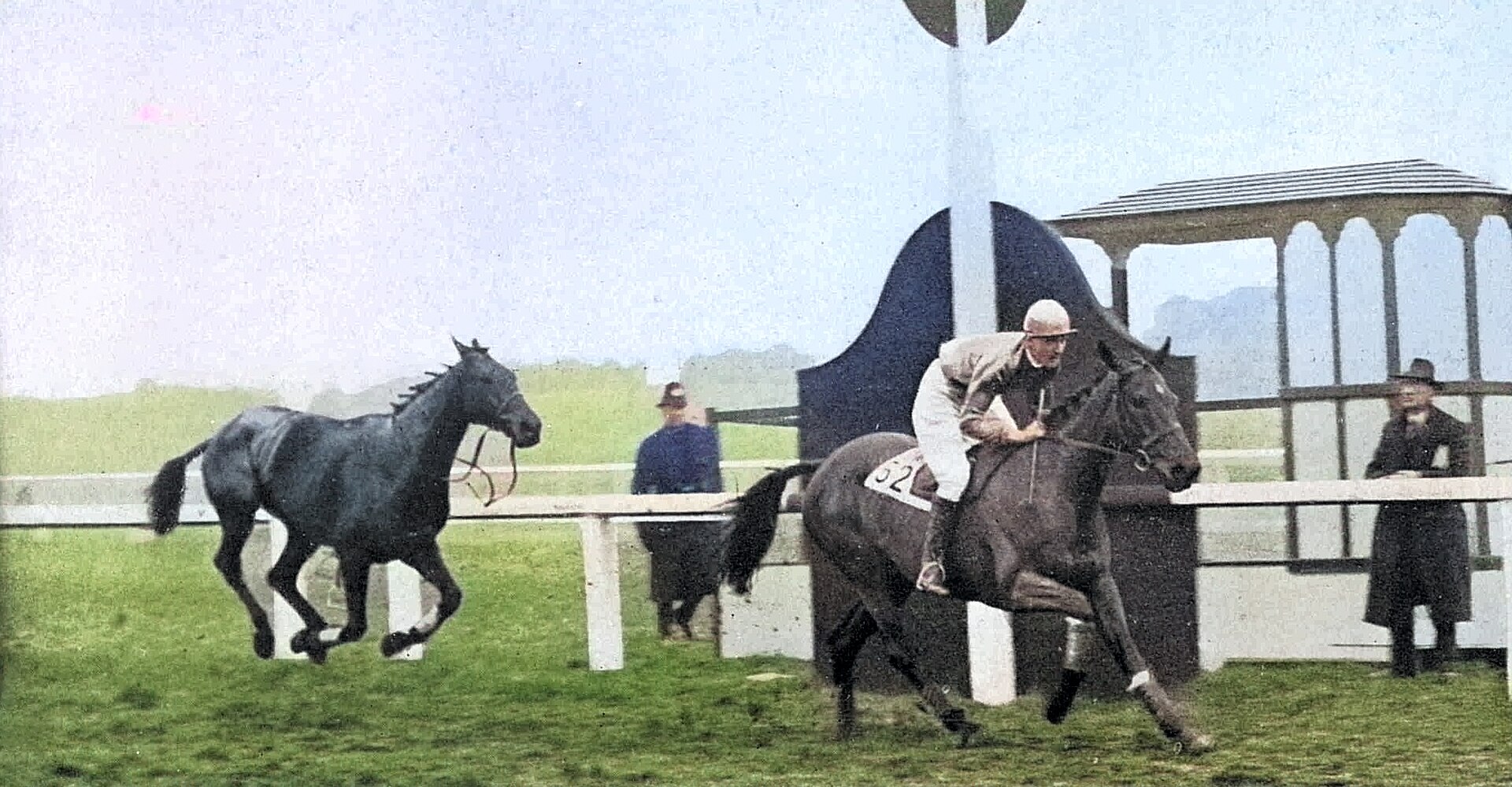

Maguelonne was still trailing at the first fence following Valentine’s Brook where it fell. May King fell shortly afterwards before Great Span lost his saddle and rider, leaving only Billy Barton, who started with 33/1 odds, and Tipperary Tim. Billy Barton had led the race for two and a half miles until the last fence where Tipperary Tim drew level. The riderless Great Span was between them and may have slightly hindered Billy Barton. Billy Barton struck the final fence with his forelegs and fell, dismounting his rider, Tommy Cullinan, leaving Tipperary Tim all one his own to head up towards the finish line at the end of the elbow.

The crowd looking on almost in disbelief at the lone outsider trotting home, but gave a huge cheer when he finally crossed the line. Tipperary Tim came in first, with a time of ten minutes and twenty three seconds, closely followed by the riderless Great Span. A remounted Billy Barton came a distant second and was the only other horse to finish.

With only two horses completing the race the 1928 Grand National set a second record, for the fewest finishers. Tipperary Tim was the only horse to have completed the race without falling or unseating its rider. His owner Kenyon, received the prize money of five thousand sovereigns as well as a cup worth another two thousand, while his horse became one of the biggest outsiders to win the Grand National. Only four others with odds as long have won the race since, Gregalach a year later in 1929, Caughoo in 1947, Foinavon in 1967, and Mon Mome in 2009.

There were scathing reports in the press, which described the race as “burlesque steeplechasing”, and many writers stated that a Grand National should not be won merely by avoiding an accident. The race inspired some to become involved in the sport. The future horse racing commentator Peter O’Sullevan laid his first ever bet on Tipperary Tim and cited it as the start of his life-long connection with racing. But he wasn’t the only one that benefitted from the horses win.

John Jo, the breeder from Cashel, wasn’t in Aintree that afternoon, he was in the mid-Atlantic Ocean, en route to the United States when he found out that his horse had won the race, having been one of only two that was able to complete the course. At 100/1 odds, this gave Ryan a good return on his £5 bet, and set him up will on the other side of the pond.